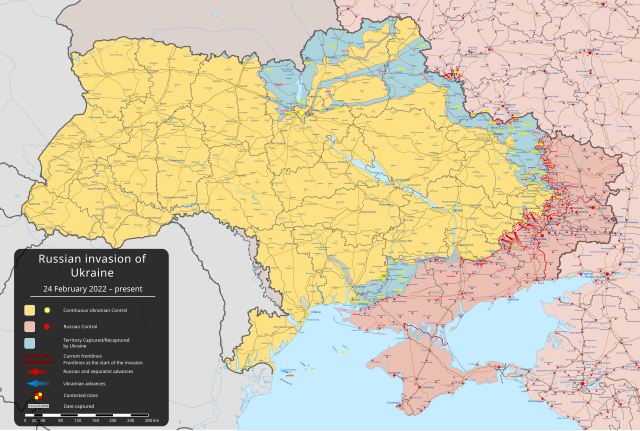

When Russian forces streamed into Ukraine and initiated a large-scale invasion in February 2022, it was predicted that Russia would establish air superiority within the first 72 hours. However, 9 months after the war started, the skies of Ukraine were still contested. Russia has since made no significant history of air superiority in more than three years of their offensive operations.

Ukraine’s ability to defend itself against aircraft and missiles has played a key role in countering Russia’s invasion. How does Ukraine’s defense systems compare to Russia, and how are Russian and Ukrainian air force modernization expected to evolve in 2026? Let us discuss them below.

Ukraine vs. Russia Military Comparison

At the start of the invasion in 2022, Russia focused on quickly destroying fixed radar, surface-to-air missiles, and command sites in the opening phase of the conflict. Most of their long-range missile strikes targeted 75 percent of Ukraine’s air defense sites, although the destruction was limited to only around 10% of Ukraine’s mobile air defense assets in the first 48 hours of the conflict. This is because most of the missiles struck sites from which Ukraine’s mobile Ground-Based Air Defenses (GBADs), ammunition stockpiles, and aircraft had already been moved, showing their failure to maintain timely target lists. Russia lacked a comprehensive targeting approach that could otherwise support their superiority and destructive effect.

Aside from the intelligence issues, the process by which Russia’s military assessed the damage level done by a particular attack was ineffective. This subsequently caused them to miss the opportunity of launching follow-up strikes to undestroyed remaining targets. Russian military commentators have pointed out that shortages in airborne early warning and control system (AEW&C) aircraft, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), drone defense systems, signals intelligence, and integrated command and control as limiting factors in establishing air superiority. Furthermore, only about half of the 15 AEW&C of the A-50 family operated by the Russian Aerospace Forces (Vozdushno Kosmicheskikh Sil—VKS) were in suitable age and working condition, falling short of the capabilities offered by their Western counterparts.

From Ukraine’s point of view, they knew the invasion and strikes were imminent from data obtained from intelligence from the United States and NATO. They showed a well-equipped, ready and well-maintained air defense capability. This includes:

- Long- and medium-range surface-to-air missiles (SAM), which give coverage for over almost all of Ukraine’s eastern airspace at medium to high altitudes.

- Man-portable air defence systems (MANPADS) and anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) to threaten low-flying aircraft and helicopters.

- Early warning radars to track Russian aircraft, and command and control systems to coordinate air defence responses.

This was a remarkable advancement on their capability when Russian forces occupied the Crimean Peninsula in 2014. After the improvement, Ukraine retained a Soviet-style structure with more ground-based air defence capabilities than a Western military of similar size.

Ukraine’s air defense system has three major advantages from the improvement:

- Increased resources led to better training, critical maintenance and repair work for high levels of readiness.

- Integration of new drone defense systems, munitions, and networking software.

- Significant Western military aid to Ukraine. Initial support was mostly non-lethal, but expanded to include military capabilities such as air surveillance along with command and control systems after Russia’s continued threat to Ukraine’s eastern regions.

Air Superiority in Ukraine War

Ukraine had some success in protecting their forces and infrastructure from the initial Russian air and missile threat. The survivability and resilience of Ukraine’s air defences when faced with Russia’s initial attacks was crucial to these successes.

Despite extensive experience in air defense or close air support missions, Russian air forces have never been pitched against a sophisticated enemy air defense system like Ukraine. Instead of attempting a US-style air superiority campaign for this particular struggle, Russia appears to have sought only limited air superiority in its plan to quickly seize Kyiv and topple the Zelenskyy government. This may be because Russia’s ground forces rely much more on artillery than on airpower.

Several reasons were identified for the failure of Russia to establish air superiority:

Ineffective Initial Strikes

Early air and missile attacks were dispersed across many targets and did not focus on critical command-and-control nodes, which are the places where military leaders direct operations, make decisions, and coordinate forces. This allowed Ukraine’s air and air-defense forces to remain operational.

Weak Non-Kinetic Integration

Cyber operations, electronic warfare, and counter-space activities had limited effectiveness and were not well synchronized with kinetic strikes or military attacks that use physical force to damage targets.

Inadequate Suppression/Destruction of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD/DEAD) Planning

Russia did not effectively target Ukraine’s integrated air defence system (IADS). Mobile SAMs survived, airfields were not cratered, and few Ukrainian aircraft were destroyed on the ground.

Poor Intelligence Utilization

Russian forces lacked accurate, timely intelligence on high-value targets, such as mobile SAM sites, key radars, command posts, and senior leadership locations.

Lack of Counter-Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Planning

Russia had no comprehensive strategy to counter Ukrainian drones and uncrewed systems, or any unmanned vehicle remotely controlled for tasks like surveillance, delivery, or mapping. This inflicted substantial losses on Russian ground units.

Despite Russia’s technical advantage, particularly in aircraft sensors and air-to-air missile range, Ukraine managed to be superior in terms of pilot aggression, skill, and a higher tolerance for losses. Russia’s most advanced fighter, the Su-57, played almost no role in the conflict. While the VKS outmatched Ukraine’s air force technologically, they did not demonstrate the same superiority against Ukraine’s ground-based air defenses. Key ISR assets like the Tupolev Tu-214R were deployed in very limited numbers, and Russia’s reliance on anti-radiation missiles proved ineffective as Ukrainian operators countered them by switching the radars off at irregular intervals.

However, within weeks of the invasion, a state of mutual air denial was established in eastern Ukraine. Ukraine denied Russia the freedom of action, but also could not maintain air superiority in the Ukraine war, as long-range Russian SAM in both Russia and captured Ukrainian provinces targeted Ukrainian aircraft in eastern Ukraine. Since then, this state has continued for crewed aircraft on both parties.

Changes in Tactics

After realizing that the Ukrainian airspace was too dangerous for crewed aircraft, the Russian military changed their tactics in the northern winter of 2022, targeting civilians and forcing Ukraine’s air defense systems to adapt. Air attacks also expanded to target water distribution facilities, petroleum processing facilities, and electricity generator infrastructures.

This dramatic shift imposed new challenges on Ukraine’s air defense plan, as they must defend both civilian infrastructure and military forces with a limited supply of air defense munitions. They needed to be able to quickly distinguish drones from cruise and ballistic missiles to prioritize the highest threats. They should also find more economical ways to defeat low-cost drones.

The Role of Drones in Ukraine and Russia Air Force Modernization

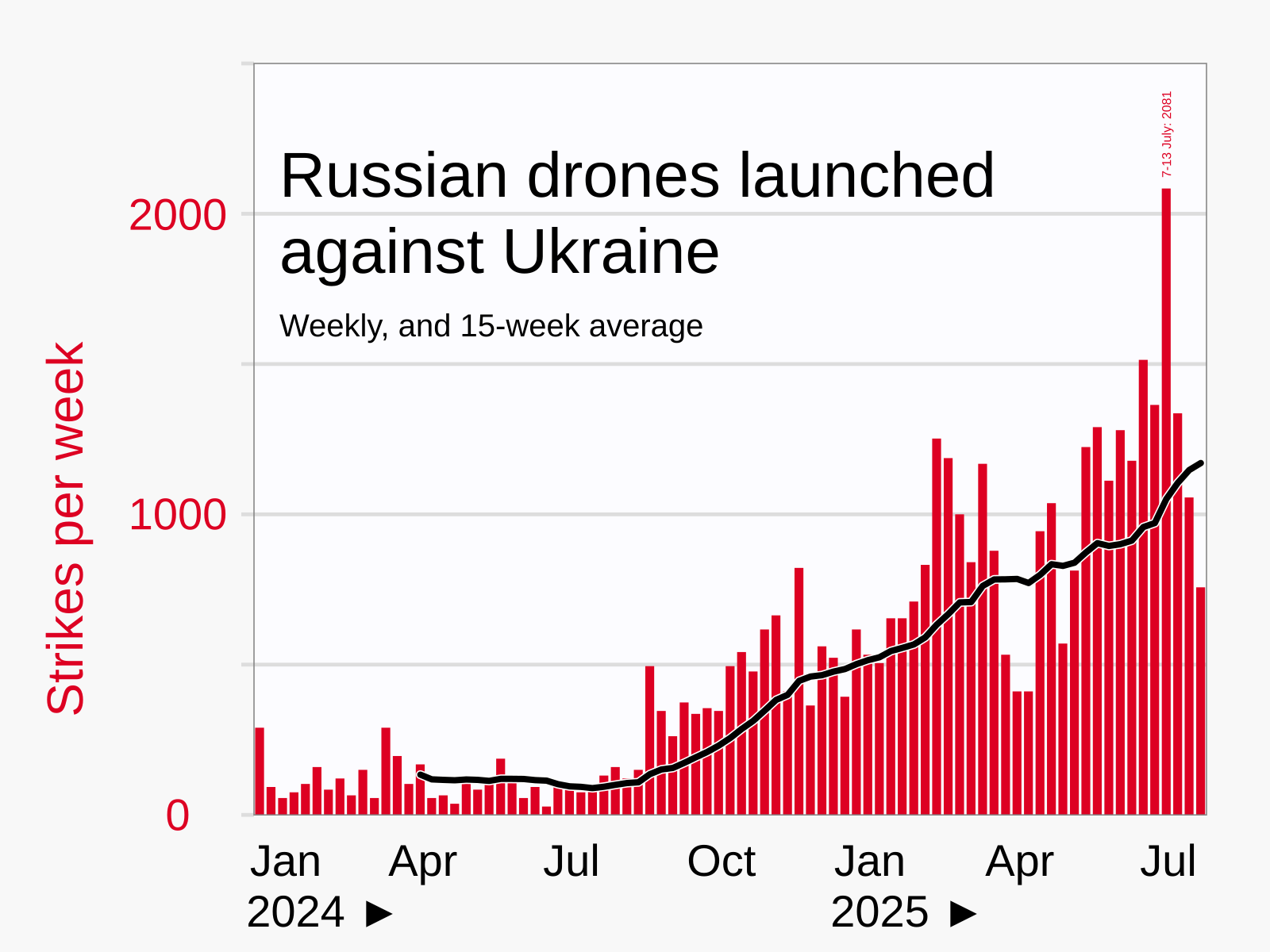

Both Russian and Ukrainian militaries mainly use these long-range suicide drones, specifically one-way attack (OWA) drones and pre-programmed kamikaze drones (single-use suicide drones) to attack deep into enemy territory. These drones act as low-cost cruise missiles. One of Russia’s most advanced drones in their air force modernization is the Iranian Shahed, manufactured by Russia and Iran in Yelabuga, Tatarstan.

Ukraine also had several types of long-range OWA drones such as the Liutyi, however, they were ineffective against hardened infrastructure, making them vulnerable to air defenses. Despite 70 to 90 percent of drone defense systems being intercepted and destroyed in flight, they managed to overwhelm Russia through mass deployment due to numbers and volume.

Three Phases of Drone Development

The evolution of drone defense systems in the Russian and Ukrainian air force modernization can be summarized into three major phases, each with a pursuit of innovation and countermeasures:

Phase 1 (2022): Mass adoption and decentralization

Ukraine rapidly distributed drones down to frontline units through the Army of Drones program, turning Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) into essential tools for reconnaissance and artillery guidance. On the other hand, Russia initially relied on large military drones and a centralized ISR-driven doctrine. This means Russia depended on a system where intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) information from drones, radars, and sensors was collected and controlled from higher headquarters instead of small frontline units, which turned out to be rigid and less adaptable.

Phase 2 (2022–2023): Strikes and counterstrikes

Both sides boosted air and electronic defenses, causing a high number of drones to be lost in combat. By mid-2023, Ukraine lost roughly 10,000 drones a month. Medium Altitude Long Endurance (MALE) drones virtually disappeared, while kamikaze drones began to dominate. In line with the Soviet doctrine of deep strikes, cheaper drones were launched in massive numbers to overwhelm the airspace, allowing highly capable cruise missiles to hit their targets more easily.

Phase 3 (2023 onward): Dominance of FPV drones

FPV (“first-person view") kamikaze drones became Ukraine’s primary tactical weapon, produced in tens of thousands monthly. Integrated into assault brigades, they made the battlefield transparent up to 10–20 km and proved highly effective against troops and armored vehicles despite jamming challenges.

Today, drones account for 75 percent of combat losses on both the Russian and Ukrainian sides. Although drone systems have not replaced traditional airpower, they have radically changed the conduct of combat.

Which Side Has the Advantage in 2026?

What does this mean for the airspace in 2026? While Russia outmatches Ukraine in military size and industrial weight, Ukraine has shown resistance due to the ability to stay technologically ahead, building drone defense systems and precision munitions that replace soldiers. This looks like something they will continue to implement in all future armed conflicts: using drones to redefine battle tactics, saturating defenses, and striking large-scale maneuvers.

However, Ukraine lacks the industrial base and engineering knowledge. As Russia’s resources keep increasing, Ukraine might not be able to compensate once Russia catches up with developing countermeasures. Russia has a centralized structure and UAV units like Rubicon, which gives it the advantage of a short design-deployment cycle within weeks. As stated by Artem Bielenkov, chief of staff of the 412th Nemesis Regiment, 2026 will be the year of aerial intelligence and the scaling of deep and middle-range strikes."

In 2026, the central question becomes whether Ukraine can innovate fast enough and diversify its production deeply enough to counter Russia’s massive industrial and technological momentum. The future of airpower in this war may hinge less on who has more aircraft, and more on who adapts faster in a battlespace defined by drones, intelligence, and precision strike systems.